AWG Shares Magazine

Writing, art, and more from the members of AWG

Contents

May 2025 • Vol. 1, Nr. 1

Cover:

Sarah Jane Cody

Editor's Note:

Annie Mydla

Audio:

Fracture Resistance • Alëna Korolëva

Essay:

Illustration:

Representation • Angela

Story:

Ceramic:

Art is Resistance • Val Flynn

Essay:

Meaningful Diagnosis • Mar Wilder

Trigger warning: Suicidality

Story:

The Witch on the Hill: Part 1 • Nadia T

Trigger warning: Physical violence towards an autistic-coded character

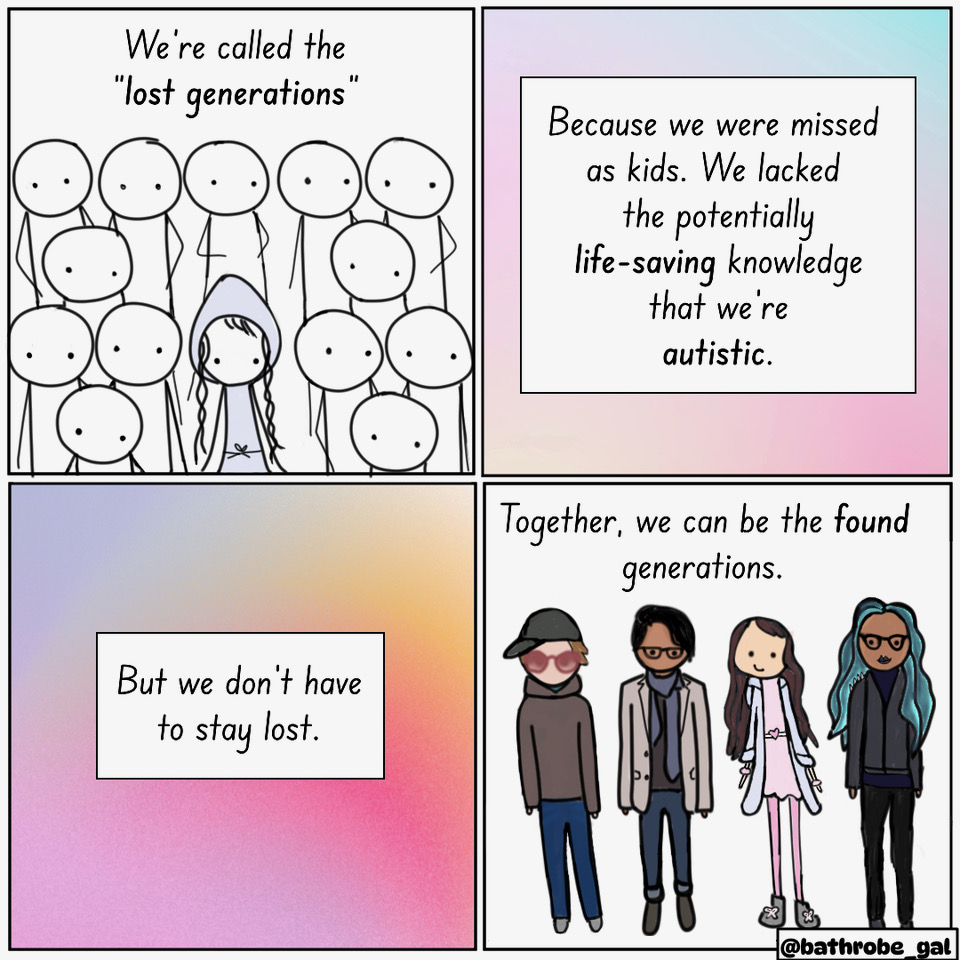

Comic:

Bathrobe Comics: Lost Generations • Sarah Jane Cody

Editor's Note

Annie Mydla

During the past four years of AWG meetings, my attention has often been called to the creativity of our members. We write, we draw, we are photographers, we are sound composers, and more. Many of us work in creative fields like the arts, education, engineering, and social services. Our creativity has contributed to our communities and boosted the effectiveness of the organizations we work for. And the creative contributions of group members to the AWG format have made it the unique source of solidarity and healing we have today.

It’s not totally surprising to me that late-identified autistic women and other marginalized genders are creatively talented. We’ve spent our lives assembling detailed outer personas with the awareness that one tiny mistake could result in big social and personal costs. And now that we know we are autistic, our creative powers are helping us to reimagine our identities. Our creativity goes deeper even than the arts. We have had to create ourselves.

Still, simply being aware of our creativity didn’t prepare me for the impact each one of these submissions would make as it hit my inbox. I laughed at the details that surprised me with their accuracy and cried in recognition of the dreadful grit in our will to carry on. Every submission deepened the feeling Andrea describes so well in “Autistic Community: Finding a Way to Exist Beyond the Lack of Representation”: This is made for me. For me and for you.

Thank you so much for making AWG Shares Magazine a reality. I encourage all readers in the AWG universe to contribute in the way that is sustainable to you today. Let’s celebrate the creativity that has allowed us to survive.

Annie Mydla

Fracture Resistance

by Alëna Korolëva

alenakoroleva.com

Fracture Resistance is a composition combining recordings made at different times of the year on Lake Ontario in order to track and trace the shifting climate. Sounds of thinning ice emerge from cracks spreading in a curving pattern. Winter guests from the Arctic arrive: long-tailed ducks call to each other. Howling winds carry the strident voices of barn swallows, diving close to the water then disappearing into the air. The piercing sounds of military jets provide a stark contrast to an ecosystem of co-operation and accommodation. Skipping stones turn the lake into a vibrating plate. Each impact creates a flexural/bending wave, radiating sound into the air, the short waves/high frequencies arriving first. These waves track the ice’s vanishing act, a harbinger of both the new season, and the seasons already lost, as climate shifts are written in the math of disappearance.

Fracture Resistance was first published in Framework, an online journal of field recording art and phonography: https://frameworkeditions.bandcamp.com/track/fracture-resistance

Autistic Community: Finding a Way to Exist Beyond the Lack of Representation

by Andrea

"Before knowing that I was autistic, I felt like I was just a species of my own."

Illustration: "Representation", by Angela

Before knowing that I was autistic, I felt like I was just a species of my own. Not only that: I felt like I barely existed. I had spent a whole life looking around me, and getting the same feeling over and over and over, no matter how different the context, how diverse my experience with people from all corners of the earth, completely different social backgrounds, etc: the feeling that the way I existed was not relatable to anyone.

I find it difficult to describe what growing up in a system and a world that do not reflect who you are means. The best way I can describe it, is that I implicitly know – whenever I go to watch a movie, whenever I meet people, whenever I walk into a coffee shop, or do anything – I just take it for granted that things are not made for me.

That they are always made for someone else. I take for granted that the world won’t reflect who I am.

I find it difficult to imagine what it must be like to not feel like that. To walk into a room and know that the rules are made for you. To watch a movie and not feel any difference between you and the characters – not having to constantly account for that difference, automatically sorting out what is normal to them and what is normal to you. How does it feel to look at the world and see yourself?

There is still so little representation of the autistic experience in culture. When it is represented, it is often deprived of nuance, or autistic-coded characters are marginal, or stereotyped. There is such little representation of the diversity of autism, and not just ethnically or religiously, but also when it comes to the myriad of ways in which our sensory experiences, passions, values, worldviews, social styles, struggles, achievements can manifest.

What does it mean to grow up without representation? It’s not just about being politically correct. It’s so much deeper than that. It means to grow up with the feeling that the world belongs to others. The lack of cultural representation is always a cultural message in itself: that you are a guest in the world – if the world was a house, you don’t own it.

Not only that: every human being, autistic or not, needs role models to grow. We need to learn from someone that resembles us, who grew through a similar experience, and found a way to exist in a healthy way (hopefully). The cultural invisibility of the autistic condition, means that a lot of us do not have that. Some people will suffer from this lack more than others.

Being autistic changes everything. What does adulthood look for us? What does a healthy life look for us? What does achievement look for us? If we are often at odds with our communities, what does belonging look for us? If the rules of neurotypical society are not made for us, how do we negotiate our difference? How do we balance our communication style with our ego, our needs with our accountability, our freedom with our responsibilities, when do we push, when do we stop, what life paths are suitable to our needs? How do we even think of time, if so many of us do not have linear lives?

As autistic people, we are, in a sense, forced to reinvent the world – to write the rules for ourselves. That is a difficult task, much bigger than simply following what is already there. Autistic communities are a space where this task can become collective.

Having lived an entire life feeling like I existed in a void of unrelatability, the first shock came for me when I met a neurodivergent mentor. I could not believe that someone had asked themself all the same questions that I asked myself (those questions that everyone shut down my whole life), I could not believe someone had built a whole life beyond the suffocating parameters of what’s supposed to be normal, I could not believe someone viewed the world the same as me, and had found a good place in it. Witnessing someone being openly and unapologetically different, and not experiencing marginalization or shame because of it, blew my mind to an incredible degree, because it introduced an entire new way of being as a possibility. Unbeknownst to me, I had just encountered the neurodiversity worldview.

The second shock came once I realized I was autistic and I joined AWG, and I felt that this group was made for me. Everything from the format, to the shared experience of the members, felt right – like a pair of shoes that finally fits. It was like a whole part of me could finally relax – suddenly there was no difference to account for, no anxiety of having to do something beyond my brain’s ability, no more constant extra work of translating myself into acceptable terms, or translating someone else’s world into mine. After a lifetime spent searching, I had indeed found “my people”. Something was “made for me”. At the beginning, this gave me a weird “double cognitive dissonance”: like a background noise that suddenly stops, the constant cognitive dissonance that I was used to since birth all of a sudden was no longer there. That in itself was unexpected, and it gave me a weird “it feels natural but unfamiliar” feeling for some time.

I always say that discovering that I was autistic definitely saved my life, and I don’t mean just discovering how my brain works (or the fact that I would have otherwise very likely ended it before 30). The discovery gave me back something arguably more valuable than physical life itself, which is the right to feel human. Growing up without feeling represented by the world, or feeling that I was constantly unrelatable to everyone around me (including other autistic people with different values and communication styles) had done that for me – it had made me feel like I was not really human, because I couldn’t see anyone else "humaning" the way I did. Having learnt that no one resembled me, I was carrying around my existence like an irredeemable cosmic mistake, and I was unable to see any real possibility for myself. I was definitely going to add to the statistics.

I still struggle to find my place in the world, and I am still in the process of discovering how to exist with this brain. But if anything, I am hopeful that I can have a place, and perhaps more importantly, that I can help create that place for other people like me. While our cultural representation is still lacking or stereotyped, community is the space where we can collectively create our own narratives by learning to articulate and celebrate all the unique ways in which we exist.

I find it difficult to describe what growing up in a system and a world that do not reflect who you are means. The best way I can describe it, is that I implicitly know – whenever I go to watch a movie, whenever I meet people, whenever I walk into a coffee shop, or do anything – I just take it for granted that things are not made for me.

That they are always made for someone else. I take for granted that the world won’t reflect who I am.

I find it difficult to imagine what it must be like to not feel like that. To walk into a room and know that the rules are made for you. To watch a movie and not feel any difference between you and the characters – not having to constantly account for that difference, automatically sorting out what is normal to them and what is normal to you. How does it feel to look at the world and see yourself?

There is still so little representation of the autistic experience in culture. When it is represented, it is often deprived of nuance, or autistic-coded characters are marginal, or stereotyped. There is such little representation of the diversity of autism, and not just ethnically or religiously, but also when it comes to the myriad of ways in which our sensory experiences, passions, values, worldviews, social styles, struggles, achievements can manifest.

What does it mean to grow up without representation? It’s not just about being politically correct. It’s so much deeper than that. It means to grow up with the feeling that the world belongs to others. The lack of cultural representation is always a cultural message in itself: that you are a guest in the world – if the world was a house, you don’t own it.

Not only that: every human being, autistic or not, needs role models to grow. We need to learn from someone that resembles us, who grew through a similar experience, and found a way to exist in a healthy way (hopefully). The cultural invisibility of the autistic condition, means that a lot of us do not have that. Some people will suffer from this lack more than others.

Being autistic changes everything. What does adulthood look for us? What does a healthy life look for us? What does achievement look for us? If we are often at odds with our communities, what does belonging look for us? If the rules of neurotypical society are not made for us, how do we negotiate our difference? How do we balance our communication style with our ego, our needs with our accountability, our freedom with our responsibilities, when do we push, when do we stop, what life paths are suitable to our needs? How do we even think of time, if so many of us do not have linear lives?

As autistic people, we are, in a sense, forced to reinvent the world – to write the rules for ourselves. That is a difficult task, much bigger than simply following what is already there. Autistic communities are a space where this task can become collective.

Having lived an entire life feeling like I existed in a void of unrelatability, the first shock came for me when I met a neurodivergent mentor. I could not believe that someone had asked themself all the same questions that I asked myself (those questions that everyone shut down my whole life), I could not believe someone had built a whole life beyond the suffocating parameters of what’s supposed to be normal, I could not believe someone viewed the world the same as me, and had found a good place in it. Witnessing someone being openly and unapologetically different, and not experiencing marginalization or shame because of it, blew my mind to an incredible degree, because it introduced an entire new way of being as a possibility. Unbeknownst to me, I had just encountered the neurodiversity worldview.

The second shock came once I realized I was autistic and I joined AWG, and I felt that this group was made for me. Everything from the format, to the shared experience of the members, felt right – like a pair of shoes that finally fits. It was like a whole part of me could finally relax – suddenly there was no difference to account for, no anxiety of having to do something beyond my brain’s ability, no more constant extra work of translating myself into acceptable terms, or translating someone else’s world into mine. After a lifetime spent searching, I had indeed found “my people”. Something was “made for me”. At the beginning, this gave me a weird “double cognitive dissonance”: like a background noise that suddenly stops, the constant cognitive dissonance that I was used to since birth all of a sudden was no longer there. That in itself was unexpected, and it gave me a weird “it feels natural but unfamiliar” feeling for some time.

I always say that discovering that I was autistic definitely saved my life, and I don’t mean just discovering how my brain works (or the fact that I would have otherwise very likely ended it before 30). The discovery gave me back something arguably more valuable than physical life itself, which is the right to feel human. Growing up without feeling represented by the world, or feeling that I was constantly unrelatable to everyone around me (including other autistic people with different values and communication styles) had done that for me – it had made me feel like I was not really human, because I couldn’t see anyone else "humaning" the way I did. Having learnt that no one resembled me, I was carrying around my existence like an irredeemable cosmic mistake, and I was unable to see any real possibility for myself. I was definitely going to add to the statistics.

I still struggle to find my place in the world, and I am still in the process of discovering how to exist with this brain. But if anything, I am hopeful that I can have a place, and perhaps more importantly, that I can help create that place for other people like me. While our cultural representation is still lacking or stereotyped, community is the space where we can collectively create our own narratives by learning to articulate and celebrate all the unique ways in which we exist.

Hi My Name Is And I’d Like To Order A Pizza

by Emmie

I’ve never liked talking on the phone. For as long as I can remember phone calls fill me with a sense of dread and panic I can only describe as totally debilitating.

Making them or receiving them, either way it’s horrible.

When I was around sixteen years old my mother decided to “help me” with my fear of talking on the phone. We wanted to order a pizza for lunch, and apparently this was my time to shine.

She handed me the phone as it was ringing and instructed me to place the order.

This was during a time when people still had house phones with the coiled cord connecting to the base of the phone, and as I stood there paralyzed, holding a ringing phone, I could have sworn that curly telephone cord was a noose. I was standing frozen by the phone and each ring felt like a step towards my execution. Dramatic? I know, but at the time I felt as strangled as Dwight’s (the character in The Office) chickens as he says, “to my chickens I’m the Scranton Strangler.”

Now for the performance of a lifetime. The line stopped ringing and a man answered the phone saying, “Papa Johns, how can I help you?” Help was absolutely needed and desperately wanted but I wasn’t sure how to ask for it.

As soon as he finished speaking, the words HIMYNAMEIS____ANDI’DLIKETOORDERAPIZZA rushed out of my mouth. I proceeded to give my entire order, not stopping until my panicked liturgy was finished. After this award-winning speech the man waited a beat and said, “First, I need your address.”

He could have told me I had 24 hours left to live and I would have been filled with more relief.

I then gave my address, after which he asked me for my order, which I gave in a monotone voice as the shame and despair continued to sink in, pouring over me in waves.

At that point I wasn’t hungry anymore and my mouth filled with stomach bile as I tried not to vomit from the nauseating and utterly devastating conversation.

I can’t remember how the pizza tasted or what happened after I hung up the phone, only that the call felt like a test and I had completely and totally failed. I’m talking 0 points out of 100, and “see me after class” failed.

I’m not quite sure why phone calls strike such fear in me. Maybe it’s because I can’t see the person’s face and don’t know how they’re reacting to my words or if I’ve said the wrong thing. Maybe it’s because I’m not sure when it’s my turn to speak which often leads to an uncomfortable silence. Maybe it’s because I don’t have enough time to prepare what I’m going to say and run through the possibilities of exactly what’s going to happen, only that I will have a limited time to respond, and I have to fervently pay attention so as not to miss anything or totally embarrass myself.

This dread is something that still plagues me to this day, and before every phone call I have to make I carefully prepare a script in my head, repeating it several times and re-wording anything that sounds awkward.

I’m not sure if I will ever feel comfortable picking up a phone, but I’m learning to tell myself that an uncomfortable or stilted conversation isn’t the end of the world, and that after I hang up I don’t need to ruminate for the foreseeable future on every single detail of the conversation, overanalyzing every pause and word spoken.

My mind likes to run wild with criticisms, replaying the call as if it was a CD stuck on a song, unable to move past a certain note, skipping back to the beginning and playing through each line all over again.

As much as I’d like to silence my phone, I’d like to silence those voices inside my head even more. I’d like to be free of the anxiety and panic, and able to move on after a “failed conversation” or awkward moment. I’m not sure how realistic that hope is, but if it ever happens, I’ll call you.

⁃ TTYL (but hopefully not on the phone), Joy

Art is Resistance

by Val Flynn

https://studio606.art

Meaningful Diagnosis

by Mar Wilder

Trigger warning: Suicidality

On most of my childhood birthdays, just before blowing out the candles, I made the same simple yet heartfelt wish—for a true friend. Looking back now, I realize that while I had friends at times, I never truly felt like I belonged. It wasn’t until my late twenties, when a clinician identified me as autistic, that I finally understood why. I learned that being autistic is not something that needs to be fixed and for the first time I began to understand myself.

For many autistic individuals, diagnosed or not, suicidality isn’t an abstract risk—it’s a constant undercurrent, often beginning as early as childhood. That was my reality. I liked watching Arthur before school and participating in after-school sports, but there were other times when I found myself threatening to jump from a second-story window. Suicidal thoughts became my mind’s way of expressing pain.

Throughout my adolescent and young adult years, I was frequently referred to different therapists, as they appeared uncertain in their ability to provide appropriate care. I repeatedly changed schools following incidents that induced shame, eventually graduating from a special education high school, where I was enrolled for “emotional disturbance.” Unbeknownst to me, I consistently engaged in social camouflaging—an exhausting effort to mimic others, to suppress my natural responses, leading to a persistent sense of hopelessness.

Looking back, there were many missed opportunities to identify my autism. I cycled through nearly every level of psychiatric care—school-based therapy, outpatient and intensive outpatient programs, partial hospitalization, residential treatment, inpatient stays. Yet I consistently responded poorly to psychiatric treatments, including evidence-based therapy and psychotropic medications. This pattern of treatment ineffectiveness could have signaled a misdiagnosis, regardless of providers’ familiarity with autism, yet no one questioned it.

Clues were abundant in my first residential psychiatric evaluation. My self-reported challenges were dismissed as "psychological cover." The clinician reported that I barely established a working alliance and maintained inadequate eye contact throughout the interview. My masking behavior, naivety, and social difficulties were accurately described, but not interpreted as autism:

- She possesses a heightened awareness of social norms and expectations.

- She desperately wants people "to like me," and to this end "I put on different faces for people."

- She lacks the necessary social identifications with real people to successfully engage her peers.

- She does not have the psychological skills - plus lacks the vocabulary - to engage in normative adolescent banter and exchanges that are the currency of this age group.

- She may not have the breadth of words necessary to fully express her thoughts and label her emotions.

- Her personal narrative lacks cohesiveness, in part because she is afraid to engage in introspection, which she rationalizes, "Not a good communicator... afraid of people... other people will judge me."

Everything was there, hiding in plain sight. The signs weren’t missed—they were misinterpreted.

Misdiagnosis wasn’t just a mistake—it was a barrier that kept me from understanding who I was for all of my youth and young adult years. It led to costly, time-consuming psychiatric treatments that left me feeling broken and unknowable. Had I been identified as autistic sooner, I believe clinicians would have shown me more grace when I made a social misstep that strained the therapeutic relationship.

Masked autism can be difficult to recognize, and while learning I am autistic didn’t erase the years of struggle or the trauma I’m still working through, it finally gave me a framework to understand myself. I am still unraveling what that means and still learning how to exist without constant masking. But for the first time, I am beginning to see myself clearly—not as broken, but as someone who deserved to be understood all along. It took just one clinician, someone willing to look beyond assumptions, to change the course of my life. Maybe my childhood wish wasn’t just for a friend—it was for someone who truly saw me, not as someone to fix, but as someone worthy of understanding and acceptance.

The Witch on the Hill: Part 1

by Nadia T

Trigger warning: Physical violence towards an autistic-coded character

Once upon a time, there lived a witch named Valeria. Her old cottage sat upon a hill surrounded by gardens, orchards and fields, and when she was content, they flourished in unmatched splendour. She lived in a time long before most modern creature comforts, but her magic allowed her to gather water, hunt and harvest crops. It was a simple life, and a solitary one, and she was happy.

The villagers at the foot of the hill left her alone. She’ll curse you, they’d mutter in warning to one another. She’ll snatch your children away, they’d whisper, their eyes darting up to her house. But there was one girl named Adele who took an interest in Valeria. For you see, Adele was also a witch.

Her parents were both concerned and fretted over her being discovered by the other villagers. Don’t practice magic! they would warn when she conjured little toadstools and made flowers bloom, laughing in delight. Adele knew she was who she was, and no amount of hiding would change that.

Still, she understood the dangers of being declared a witch. There were rumours about a woman and her daughter a few towns over who were supposedly practising witchcraft to keep the rabbits and mice from eating their crops. It was said that a figure made entirely out of metal would walk back and forth on their fields, scaring off pests. These women claimed they built the figure, and that it was called a machine. But no one believed them, and they were taken up north and left in the wilderness, permanently exiled.

When Adele heard that story, she was devastated; Adele’s parents were terrified. Knowing there was little they could do to stop her from practising magic, Adele’s parents made her promise to only cast spells at home, and to be a good girl when she went outside. So, Adele was a good girl. She smiled and waved at her neighbours and she didn’t use magic. She even stopped moving her body in ways that felt natural to her so that she wouldn’t attract unwanted attention. She was a proper little lady.

Nonetheless, Adele would often stop playing to stare up at Valeria’s house longingly, wanting to meet her and learn from her. Even she was a little scared of the witch, though, because the villagers, including her parents, would talk about how dangerous she was, and how she was just like the two women who had been exiled. The only thing stopping a mob from seizing Valeria and dragging her to a stake in the centre of town was their fear of her capabilities. Since no one in the town knew what Valeria could do, the rumours had become wilder and more improbable over the years. Some said she could control the weather; others claimed she could talk to animals, especially snakes and goats, as those were the Devil’s children. Whatever she could do, no one wanted to find out by incurring her wrath.

And so, life went on. Fear had become a constant companion in Adele’s town, but that was normal. Everyone kept their heads down, and for the most part, they pretended Valeria did not exist. It was almost as if she were a boogeyman created by the people themselves. Some parents even used the witch to scare their children into behaving, saying Valeria would get them if they whined for more sweets.

Their small corner of the world was perfectly ordinary and comfortable for a time, until Adele’s little brother, Benjamin, fell ill. No cold compress could lower his fever, and when he shivered in bed, no pile of blankets could warm him. He refused to eat for many days, and the girl and her parents watched in desperation as he wasted away. Time passed, and Adele’s brother got worse and worse.

And so, Adele gathered her courage and decided to seek out Valeria. She waited until it was nighttime, for she knew her parents would never let her meet the witch. When the moon was high in the sky, she snuck out the back door with a small bouquet of flowers. Her quiet footsteps echoed down the deserted streets as she ran toward the hill, her dress billowing behind her.

Through the orchards she ran, the smell of fresh apples and peaches making her stomach growl.

Through the grassy fields she ran, and she longed to lie in them.

Through the flowery gardens she ran, and she wanted to pick the beautiful poppies and peonies. By the time Adele arrived at Valeria’s front door, she was tired, sweaty, and covered in twigs. Her little hand trembled, but she knocked on the door, her fist colliding with solid oak. No one answered. Adele waited. And waited. She knocked again, and an eye appeared in the peephole, glinting in the moonlight.

“Who are you?” Valeria said.

“My name is Adele. I’m from the village. My brother is sick. Please, can I come in?”

The hinges on the old door squeaked as it opened, revealing a one-room house illuminated by candles. It was somehow both clean and incredibly messy, not a speck of dust on any surface, but books were piled high. Dried flowers and herbs were hanging from the ceiling, and, somewhere in the corner, a cauldron bubbled. Adele was stunned; she never thought that she would get to satisfy her curiosity.

The witch was patient as Adele collected herself and made her way inside.

The smell of rosemary, lavender and old wood filled her nose. As Valeria got closer to the light, the girl saw that she was just an ordinary woman with brown hair streaked with grey. Her face was haggard, but her eyes were keen and bright, taking in her brave visitor.

“You’re not scared of me,” Valeria said. “I am a little bit. I’ve heard scary things about you. But you’re like me,” Adele said with wonder, and as she spoke, the buds within the bouquet she carried began to bloom.

“I’ve never once met another witch,” Valeria said, “at least not for twenty-five years. How surprising. So, you can make flowers bloom. What else can you do?

“I can make toadstools grow, too.”

“You learned how all on your own?”

“I did!”

“Hmm.”

The witch held her chin. “You’re talented for one so young…but you must know by now that the townsfolk don’t take kindly to those who are different.” Adele nodded her head and sighed. Valeria was rocking back and forth and flexing her fingers, the girl noticed. It reminded her of her own movements; the way she would blink her eyes to comfort herself and twirl in a circle when she felt joy. They were alike in more ways than she had assumed.

“But I am the way I am because that it how I was made,” the girl said, her expression firm, “and that’s that. Why should I get in trouble when I haven’t done anything wrong?”

“Why, indeed,” Valeria said, and there was a mischievous glint in her eyes. She paused. “Now, you said your brother is sick?”

“Yes. He has a fever and he’s not eating.”

“Well, then,” the witch said. “I have something for that.” And she handed the Adele a twig with leaves that were such a bright shade of blue green that the girl was dazzled in the dimly lit room. “Boil a leaf in water once a day for three days, give it to him to drink, and he’ll get better.”

Adele was filled with hope, and she thanked Valeria, tears of gratitude flowing down her cheeks.

For the next two nights, Adele boiled a leaf in secret outside, and Benjamin drank the medicine it made. By the third night, he was almost fully healed from his sickness. As Adele boiled the leaf for the final dose of medicine, her mother and father caught her.

“What are you doing?” Her mother held a lantern up at the girl.

Adele knew she could only tell the truth. “I’m making medicine. He’s getting better!”

Her parents looked in the pot that boiled over a small bonfire. Inside, a leaf spun on the surface, and the water within shimmered.

“Where did you get this leaf?” her father said, frowning.

Adele sighed, once again deciding to be truthful. “Valeria gave it to me.”

Her mother and father were stunned into silence. Then: “Get inside!” “But the medicine is working! He’s getting better. And she’s not mean or scary! She’s kind, and she helped us without asking for anything in return!”

They would not listen to her.

The next day, Adele was forbidden from leaving the house. Her parents watched her in shifts, and she withered under their glares. They had thrown out the medicine. Benjamin’s health declined sharply over the next several days, and soon he had a fever again. For the first time in her ten years, Adele felt a sense of true helplessness.

One night, Adele waited until both her parents were snoring. Then, she borrowed a lantern and snuck out again. It was a moonless night, and the lantern did little to light her way. Her intuition guided her, and her muscles remembered the path to the witch’s house.

A feeling of doubt blossomed in Adele’s chest. Was she doing the right thing? What if her parents were right all along? But she quickly squashed those thoughts. There was no reason to suspect Valeria had ulterior motives; after all, she had been so quick to help, and the effects of that help were obvious. No, Adele thought. I know I’m right. Everyone else is wrong.

It was almost as if Valeria was expecting her this time, for she did not have to knock; the door creaked open on its own, revealing the witch’s silhouette as she paced back and forth on the floor.

“Hello, Adele. I thought you would come back.”

“Hello, Valeria.”

“I take it you were caught.”

“Yes,” Adele looked down at her feet. “The medicine worked, but Mother and Father got upset and stopped me. I couldn’t give him the final dose.”

“Oh dear,” Valeria said. “Then we must start over.” She walked over to her hanging herbs and pulled down another twig with vibrant leaves and handed it to Adele. “Repeat the three doses like last time.”

“Thank you,” Adele said, her voice wavering. “I’ll try again.” She hugged the witch.

Valeria wrapped her arms around the girl. “You’re very kind and very courageous. Now hurry, he doesn’t have much time.”

Adele startled at that statement; realizing the truth in it and the direness of Benjamin’s situation, she left without saying a proper goodbye, too focused on her mission.

When Adele arrived at village, she saw a light in the window. As she neared her house, the light began to move, then Adele’s mother appeared in the doorway, a candle in her hand. “Adele! This is the final straw!” The girl’s heart hammered in her chest at her mother’s tone. “Your father is so angry that he went for a walk. Come here!”

“No,” Adele said softly. “What was that?” Her mother’s voice was dangerously low.

“I said no! You won’t listen to me! I won’t go in until you do.”

“Adele! Stop talking back and get inside! Now!”

Adele’s mother grabbed her arm and tried to drag her inside, but the girl clenched her fists, and the ground began to form around her feet, cementing them in place. “No! I’m not going!”

In all the ruckus, Adele didn’t notice Benjamin standing in the doorway, clinging to the frame and watching them, until he begged them to stop fighting. His little face was pale and scared, and there were dark circles under his eyes.

“Sweetheart! What did I say about getting out of bed?” Adele’s mother ran to him, scooping him up and carrying him through the door. It was the only chance Adele needed. She ran. She ran from her mother, she ran from her father, she ran from the villagers. She ran until her legs burned and her throat ached from her gasping breaths. And eventually, she found herself back at Valeria’s house.

This time, she did need to knock. The witch answered her door, her sleepy expression quickly melting into concern. She watched and waited.

Adele was so exhausted that she could barely speak. “Help,” was all she could manage. “Please. They won’t listen.”

“I’ll come with you this time,” Valeria said. Once outside her house, she grabbed a shabby looking broom that was propped next to the front door. “Hop on.”

Adele’s determination outweighed her fear, and she rode the broom back to the village with Valeria.

The darkness of nighttime was shifting into a dim sunrise as they travelled in silence. As Valeria descended, the first rock hit her. Then, a second one struck her temple, drawing blood. There was a small crowd of villagers gathered around Adele’s house, including the person who threw the rock, who cried, “Filthy witch! You’re corrupting an innocent!”

“Cursed woman!” another voice yelled.

More rocks flew toward Valeria, but she was ready this time. They paused in their trajectory, then flew in the opposite direction, though they hit no one in the crowd.

Valeria landed and helped Adele down. Then she strode forward, her chin lifted in proud defiance and eyes blazing as she faced them.

“Villagers!” The witch’s voice was strong and clear as she addressed them. “For too long you have feared me, but there is nothing to fear. For too long you have spread lies against me and other witches without any grounds. But that stops today. For I’m not cursed. I’m not filthy. I’m not evil. I’m just a person who practices magic. And I’m here to help one of you, her brother.” She gestured to Adele.

“Lies!” Adele’s mother said from the head of the crowd. “You’re an evil influence! You’re poisoning our child!”

“I’m healing him. Did he not seem better for a time? Did he not get worse when the medicine stopped?”

“She has a point,” a voice said. Adele watched in shock as her father emerged from within the crowd, stopping to stand beside her mother. “Those days when Benjamin took the medicine… It was the first time he smiled and ate a meal in weeks. And his fever came back as soon as it stopped. I’ve done a lot of thinking. While I’m unhappy my daughter defied me, I’m happy she did it for the right reasons.” He turned to his wife. “Agatha. I know you’re afraid. But maybe there’s reason not to be.”

The crowd gasped as Adele’s father walked toward Valeria and held out his hand. “Valeria, consider this a proper introduction. I’m Samuel, this is my wife, Agatha, our son, Benjamin is ill, and of course you’ve already met Adele.”

Valeria stared at Samuel’s hand. When she finally grasped and shook it, her eyes were wet. “Nice to meet you.”

“You’ve endured much cruelty at our hands. I can see now that our prejudice blinded us to the truth: that you’re a good woman.”

“Samuel!” Agatha said.

“No, my dear. It has to be said.” Agatha froze, then furrowed her brows. Samuel turned back to the crowd. “Let me ask you all a question: Does anyone have proof that Valeria stole your children?”

The villagers were silent, and he continued, “Does anyone have definitive proof that she cursed you or someone you know?” The crowd murmured, but no one spoke up. “Then why would you blame her with no evidence of her wrongdoings? Does that not seem nonsensical?”

“It doesn’t make sense,” an old woman agreed.

“Right, it doesn’t. We have built our false beliefs on a foundation of sand, and the truth is a wave that is washing them away. As the tide renews both land and sea, the truth can start us anew. Fresh. Open to learning more.”

Adele watched Samuel with bright eyes, and at the end of her father’s speech, she rushed over and hugged him tightly. He returned the hug, smiling down at her.

“Now, I would understand if you resent us, Valeria, but please know that our actions were not out of malice, only ignorance. I am sorry.”

Valeria offered a watery smile. “I forgive you all, both for your sake and mine.”

A change in the air settled around everyone, and as a crisp breeze descended upon them Samuel’s expression turned grave. “Valeria, would you please help my son?”

The witch seemed to glow from within, and she nodded, producing the now familiar medicinal leaves from her pocket. Samuel led her behind his house where she boiled the leaves, the fire turning her face and hair a fiery orange. Adele thought she looked beautiful in that moment: kind, strong and loving.

Agatha had been watching Samuel and Valeria this whole time, her eyes wary. But there was a calm that had settled over her for the first time in a long while. She yawned, and Adele saw that there were bags under her mother’s eyes, her face wan. A pang of sadness hit the girl as she thought about her mother’s fear and helplessness at Benjamin’s illness. She took her mother’s hand. Agatha wrapped her hand around her daughter’s, squeezing it.

“It’s worth a try, I suppose,” Agatha said to no one in particular, the ghost of a grin on her lips.

And so, Benjamin took the medicine again, and by the fourth day, there was colour in his cheeks, and he was smiling and playing with his sister, his parents and his friends.

Some said it was a miracle, but not all the villagers were convinced. And while some townsfolk welcomed Valeria to help them, others thought there was something more sinister at play. She made the boy sick to begin with, then healed him to trick us into trusting her, some said. And she’ll bring more misfortune, just you wait and see.

The villagers that sought out Valeria’s help saw that she could fix many problems, whether it was a broken plate or a broken bone—sometimes it was a broken heart. The witch cured diseases and mended injuries with ease, her vast knowledge evident as she gently and calmly helped the people. Months passed, and over time more of the townspeople began to trust her.

Adele’s family got close to the witch, and they often had tea together, talking about everything and nothing and sharing thoughts and dreams. One day, when the sky was a brilliant blue and the warm, summer sun baked the earth and nourished the flowers, Valeria put down her teacup and said, “I would like to take your daughter on as her mentor.”

Hearing this, Adele perked up from her seat on the floor where she was drawing on a small chalkboard. Valeria continued, “Your daughter is brilliant, and I think she could be even more brilliant with some guidance from an experienced witch.”

Samuel and Agatha exchanged a thoughtful look. “We’ll give it some thought,” Agatha said. “Take all the time you need to decide.”

It didn’t take long for Adele’s parents to agree to Valeria’s proposal, and the next day, Adele walked to Valeria’s house, enjoying the bright daylight and passing butterflies, the sky full of cottony summer clouds. It was the first time she was going to Valeria’s cottage in plain sight, Adele realized, which was a sign of how much circumstances had changed.

Valeria was waiting for her outside, sipping a neon potion at a rickety old table. Her eyes lit up when she saw Adele.

“Hello, Adele! I can’t wait to get started.” “Me too!” Adele said, beaming. For now, Adele was just a young witch, eager to learn and perhaps a little naïve. But over time, Valeria thought, Adele was sure to change the world.

“Valeria? Are you alright?” The witch noticed that she had been lost in thought. She nodded with a self-deprecating laugh. “Forgive me. I’m just excited to teach you.” They had both been through so much and longed for the peaceful days ahead of them. It was a foreign feeling not having to worry about the villagers’ suspicion, Valeria thought. She could scarcely believe that she had managed to befriend dozens of them and help even more; it was almost as if she were dreaming, and at any moment she would be faced with the cruel reality of the waking world.

And though there were murmurs of conflict on the horizon, Valeria had a plan for when disaster struck. The witch knew that she could count on her own abilities—and those of some very powerful and skilled old friends. Nevertheless, despite her elation at this chance to mentor a student, anxiety gnawed at her stomach. One day, Adele would need to use her skills in battle. The harshness of a world where that was necessary saddened Valeria. It was as her own mentor once said, “Force can only be met with force.”

A quiet, peaceful world was only a dream, if a beautiful one. A dream that would not last long.

Bathrobe Comics: Lost Generations

by Sarah Jane Cody

https://instagram.com/bathrobe_gal